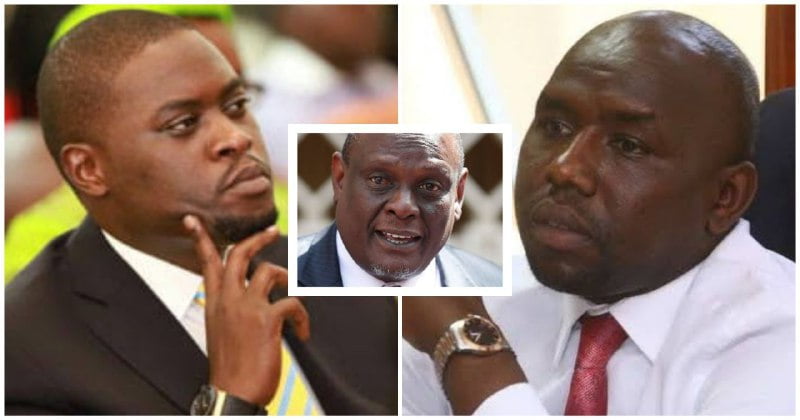

The United Democratic Alliance (UDA) is facing internal tension after Secretary General Hassan Omar openly criticized Interior Cabinet Secretary Kipchumba Murkomen for designating the Muslim Brotherhood as a terrorist organization.

Speaking at a pro-Palestine event in Nairobi, Omar rejected the move, warning that it alienates the Muslim community in Kenya and undermines broader geopolitical interests.

His fiery remarks have ignited a storm over Kenya’s counterterrorism policies, foreign alliances, and the government’s balancing act between religion, politics, and national security.

Why Hassan Omar Defended the Muslim Brotherhood

Hassan Omar’s comments were not casual remarks. He addressed thousands of Muslims gathered at Uhuru Park for a solidarity rally with Palestine. His message was clear. Murkomen’s decision to gazette the Muslim Brotherhood was, in Omar’s view, misguided and damaging.

“I saw my brother gazette the Muslim organisation as a terrorist group. In my view, I do not share that position,” Omar declared. “If anything, I believe we should instead gazette the Zionist State of Israel as a terrorist organisation.”

By turning the debate on its head, Omar shifted the focus from the Brotherhood to Israel, a move calculated to resonate with Kenya’s Muslim community. He accused the government of ignoring the real oppressor in global conflicts while targeting a religious movement that millions of Muslims identify with, even if they do not agree with all its methods.

Omar also pressed Kenya to reconsider its foreign policy stance. He argued that Kenya has deeper economic and cultural ties with the Muslim world than with Israel. For him, Murkomen’s decision risks isolating Kenya from countries that could be critical allies in trade, security cooperation, and regional diplomacy.

The Political Weight of the Muslim Brotherhood Debate

The Muslim Brotherhood is not just any movement. Founded in Egypt in 1928, it has grown into a global Sunni Islamist organisation with branches and affiliates in multiple countries. Its philosophy blends Islamic revivalism with education, charity, and political activism. For its supporters, it symbolizes resistance against oppression and Western interference in Muslim nations.

But critics point to its darker side. Over decades, the Brotherhood has been accused of spreading extremism, enabling violent offshoots, and using democracy as a tool for power rather than a principle. This has led to its banning in several nations, including Egypt, Saudi Arabia, and the United Arab Emirates.

Murkomen’s decision to list the Brotherhood under Kenya’s Prevention of Terrorism Act places the country in line with governments that see the group as a threat. The gazette notice also included Hizb-ur-Tahrir, another Islamist organization, further cementing Kenya’s position.

The legal implications are severe. Once an organization is designated a terrorist group in Kenya, all its activities are banned, its assets frozen, and any form of support—financial, logistical, or ideological—becomes a criminal offence.

Religion Versus Security in Kenyan Politics

Hassan Omar’s public outburst has laid bare a recurring fault line in Kenyan politics—balancing religion with national security. For Muslim leaders, Murkomen’s move represents state-sanctioned hostility toward Islam. For security officials, however, the listing is a necessary step to protect Kenya from extremist infiltration and radicalisation.

This clash reflects deeper questions. Should Kenya’s counterterrorism strategy be guided purely by security intelligence, or should it also consider religious and diplomatic sensitivities? Omar clearly believes the government is leaning too heavily on Western narratives about Islamist groups, while ignoring the perspectives of Muslims both locally and globally.

By suggesting that Israel should instead be declared a terror state, Omar tapped into widespread anger over Gaza and Palestine. His position, however, puts UDA in a tight spot. The ruling party now faces internal contradictions between its Muslim leaders and senior officials like Murkomen who prioritise security alignment with Western allies.

What Happens Next for Kenya’s Foreign and Security Policy

The fallout from this row could reshape Kenya’s foreign policy. If Omar’s call gains traction, Nairobi may come under pressure to review its relationship with Israel. This would have major implications for Kenya’s international standing, especially given the country’s strong ties with the United States and European Union—both key allies of Israel.

At the same time, doubling down on the Brotherhood ban may increase tensions with local Muslim communities, particularly in the Coast and North Eastern regions where the group enjoys sympathy. Politically, this could erode UDA’s support base among Muslims, weakening the party ahead of future elections.

Murkomen, on his part, remains unmoved. His gazette notice stated that the order would remain in force indefinitely unless overturned in court. This means the Brotherhood and Hizb-ur-Tahrir will stay banned until a legal or political intervention reverses the decision.