Parliament has unveiled a new list of 60 nominees for the 2025 Conferment of National Honours, a move that has sparked fresh debate about Kenya’s culture of political patronage. The list, dominated by elected leaders, will receive their decorations during the Mashujaa Day celebrations in Kitui County.

Among the nominees are Minority Whip Junet Mohammed and Senator Ledama Olekina, both influential political figures. Eleven senators and 35 Members of Parliament made the cut, while 14 nominees are senior government officials.

The awards include the Elder, Chief, and Moran of the Order of the Burning Spear (EBS, CBS, MBS). While Parliament insists the process is transparent, critics see it as another example of Kenya’s honours system being manipulated by the political elite to reward loyalty rather than merit.

Understanding the Conferment of National Honours in Kenya

The Conferment of National Honours is one of the country’s most symbolic traditions. Enshrined in the National Honours Act of 2013 and Article 132(4)(c) of the Constitution, it allows the President to recognize individuals for exemplary service, heroism, leadership, or national contribution.

The Purpose Behind National Honours

The honours are meant to celebrate citizens who go above and beyond in their service to Kenya. Recipients can come from any field — public service, academia, sports, business, or the arts. The awards are structured in clear hierarchies, with the Order of the Golden Heart of Kenya being the highest distinction.

The process involves several advisory committees — at the national, county, parliamentary, and judicial levels — which review and recommend names to the President. Before final approval, the list is published to invite public comments or objections.

In theory, this should ensure transparency and fairness. But in practice, political influence often overshadows merit.

How Political Loyalty Undermines the True Spirit of National Recognition

Kenya’s honours system has increasingly turned into a political reward scheme. Critics say successive administrations use the awards to cement loyalty or thank allies.

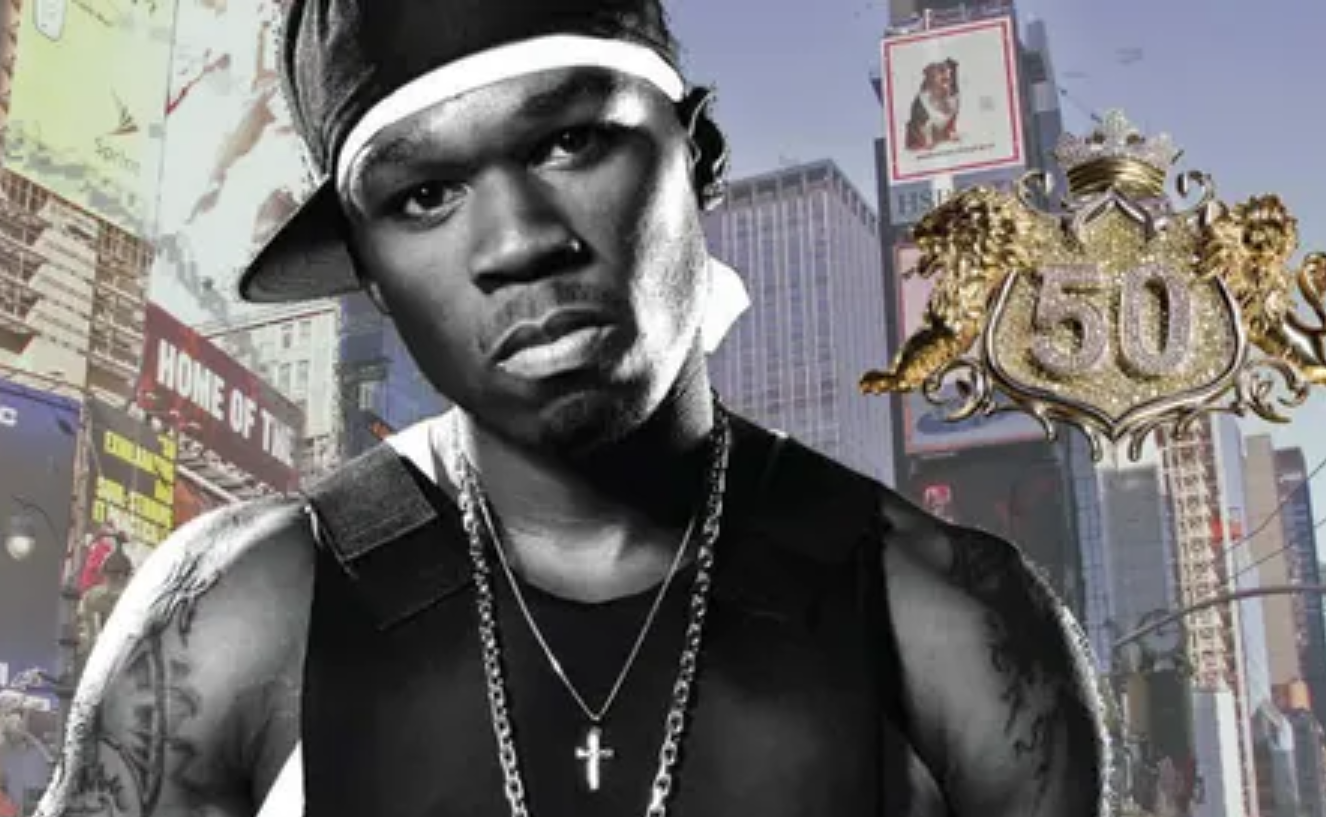

For instance, parliamentary leaders such as Junet Mohammed, Silvanus Osoro, and Gladys Boss have been nominated under the Chief of the Order of the Burning Spear (CBS) — the same recognition once reserved for individuals who made extraordinary national contributions.

Instead of celebrating innovation, heroism, or service to humanity, the honours list now reads like a political roll call. Civil society groups argue that the awards have lost meaning, reduced to mere tools for political appeasement.

This trend echoes a broader national concern: Kenya’s culture of rewarding political survival rather than integrity or excellence.

Self-Nomination and Institutional Bias

Perhaps the most glaring flaw is the conflict of interest within the nomination process. The Parliamentary Honours Advisory Committee, for example, consists of legislators and parliamentary staff — the same individuals now appearing on the nominees’ list.

How can Parliament objectively vet itself? Critics question the legitimacy of lawmakers recommending their colleagues, or even themselves, for honours. This self-congratulatory practice undermines public trust and turns what should be a solemn act of national gratitude into an insider’s celebration.

The inclusion of parliamentary clerks, directors, and even administrative officers in the list has raised eyebrows. Many Kenyans now believe that national recognition is no longer earned through service but secured through proximity to power.

Forgotten Heroes in a Politicized System

Behind every political headline are thousands of unsung heroes — teachers in remote areas, medical workers who save lives in underfunded hospitals, and youth activists fighting corruption. Yet, few of them ever receive national honours.

Instead, the same names — politicians, bureaucrats, and powerful families — dominate every list. For instance, Mary Wanyonyi Chebukati, widow of former IEBC chair Wafula Chebukati, was nominated for the Moran of the Order of the Golden Heart (MGH) for her role at the Commission on Revenue Allocation. While her service may be commendable, the optics reinforce the perception that high-profile figures remain the primary beneficiaries.

This elitism alienates ordinary Kenyans, for whom the honours once symbolized national unity and moral leadership.

Awarding Controversial Figures and Diluting Integrity

Public outrage has often followed when honours are conferred upon controversial politicians or officials facing corruption allegations. The awards, meant to symbolize integrity and sacrifice, are now being handed to individuals whose records are under public scrutiny.

The National Honours Act allows the revocation of awards for misconduct or moral failure, yet this clause is rarely enforced. Not a single high-profile politician has had their award withdrawn, even when implicated in scandals.

This selective enforcement erodes the credibility of the entire system. When honours are given to those who have failed in public trust, they lose their moral weight and become mere political ornaments.

Why the System Needs Urgent Reform

Kenya’s conferment system urgently needs an overhaul to restore dignity and trust. Experts recommend that the Honours Advisory Committees be fully independent, free from political interference, and composed of representatives from civil society, academia, and professional bodies.

Additionally, the vetting process should be transparent, with full public disclosure of the nominees’ achievements and any objections raised. True recognition should be based on measurable contributions, not connections.

By making these changes, the government could realign the Conferment of National Honours with its original intent — to celebrate selfless service, integrity, and patriotism.

A Symbolic Award or a Political Trophy

The Mashujaa Day celebrations in Kitui will once again showcase Kenya’s colourful traditions of honour and recognition. Yet, for many citizens, it will also be a reminder of how far the system has drifted from its noble roots.

The honours are supposed to unite the nation by highlighting the best among us. But when political loyalty becomes the key qualification, the awards lose meaning — and the title “hero” becomes just another political badge.

If the state continues down this path, the Conferment of National Honours risks becoming a hollow ritual — one where political elites decorate themselves while the true heroes of Kenya remain invisible.

In the end, the integrity of national recognition depends not on the prestige of the ceremony, but on the honesty of those who bestow it.