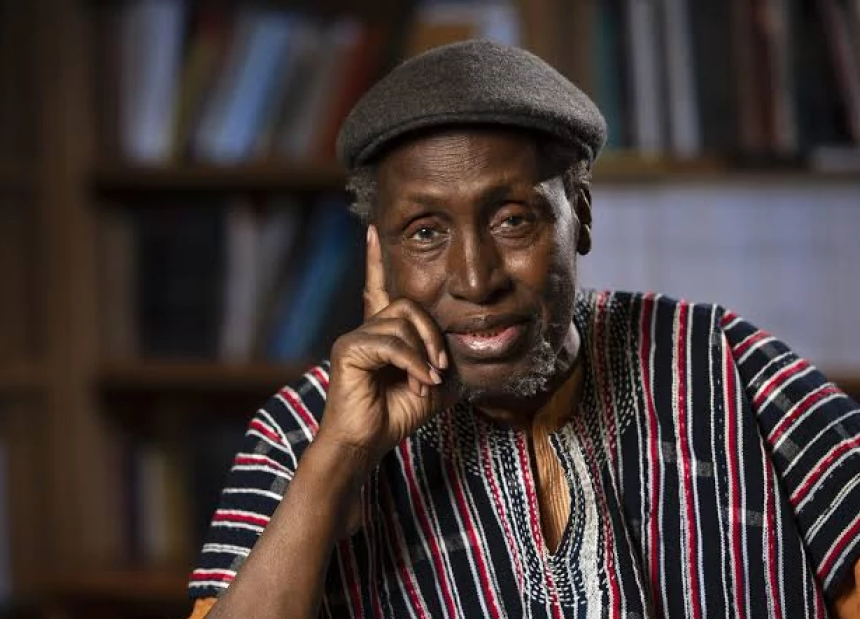

The literary world is in mourning following the peaceful passing of Professor Ngũgĩ wa Thiong’o, the iconic Kenyan novelist.

Playwright, essayist, and fierce advocate for African languages, who died on Wednesday, May 28, 2025, at the age of 87.

His death marks the end of an era for African literature and global post-colonial thought.

Indeed, leaving behind an indelible legacy of groundbreaking narratives, profound critical insights, and unwavering intellectual courage.

Often tipped as a perennial contender for the Nobel Prize in Literature, Ngũgĩ’s life was a testament to the power of words to challenge oppression.

Additionally, reclaim identity, and articulate the complex realities of a continent emerging from colonialism.

From his early works in English to his defiant shift to writing in Gikuyu, his mother tongue, Ngũgĩ’s journey was inextricably linked to the political and cultural liberation of Africa.

From Limuru to Literary Stardom: Early Life and Education

Born James Ngũgĩ in Kamiriithu, Limuru, Kenya, on January 5, 1938.

Ngũgĩ wa Thiong’o grew up amidst the tumult of the Mau Mau uprising against British colonial rule, an experience that would profoundly shape his worldview and literary themes.

He received his early education at local mission schools before attending Makerere University in Uganda.

A prestigious hub for East African intellectuals, where he earned a BA in English. He later pursued further studies at the University of Leeds in England.

It was during these formative years that his literary voice began to emerge and was characterized by a keen observational eye.

In addition to a deep understanding of human suffering and a burgeoning anti-colonial consciousness.

A Voice for the Oppressed: Early Works and Political Themes

Ngũgĩ’s literary career began in English, quickly establishing him as a powerful new voice. His debut novel, “Weep Not, Child” (1964), was the first novel in English published by an East African.

It poignantly explored the impact of the Mau Mau rebellion on a young boy’s family and education.

This was followed by “The River Between” (1965), which delved into the cultural clash between traditional Gikuyu society.

And the advent of Christianity, and “A Grain of Wheat” (1967), a complex narrative examining the disillusionment and betrayals of the post-independence era.

These early works cemented his reputation as a master storyteller, skillfully weaving personal narratives with the larger political and social upheavals of his time.

They laid bare the scars of colonialism and the challenges of forging a new national identity.

The Defining Shift: Decolonizing the Mind and the Language Question

A pivotal moment in Ngũgĩ’s career, and indeed in African literature, came in the late 1970s.

After engaging deeply with the concept of “decolonizing the mind,” he made the radical decision to abandon English.

The language of his colonial education, and he committed to writing exclusively in Gikuyu.

This shift was not merely an artistic choice but a profoundly political act, aimed at asserting linguistic sovereignty.

And making literature accessible to his own people, rather than primarily for a Western audience.

His first novel written in Gikuyu, “Caitani Mũtharabaini” (1980), translated into English as “Devil on the Cross,” was famously written on toilet paper during his detention without trial.

This act underscored his commitment to his linguistic principles, even under severe duress.

Imprisonment, Exile, and Unwavering Activism

Ngũgĩ’s commitment to social justice and his increasingly sharp critiques of the post-colonial Kenyan government led to severe repercussions.

He was subsequently arrested and detained without trial for over a year at Kamiti Maximum Security Prison.

His release in December 1978 did not bring an end to the harassment.

He was dismissed from his professorship at the University of Nairobi and forced into exile in 1982 to escape further persecution.

Despite decades in exile, primarily in the United States where he held distinguished professorships at Yale University and the University of California, Irvine.

Indeed, Ngũgĩ never ceased writing or advocating for human rights and linguistic liberation.

His seminal non-fiction work, “Decolonising the Mind: The Politics of Language in African Literature” (1986), became a foundational text for post-colonial studies globally.

Other significant works from his exile include “Matigari” (1986), and his acclaimed memoirs, “Dreams in a Time of War” (2010).

“In the House of the Interpreter” (2012), and “Birth of a Dream Weaver” (2016).

A Legacy of Liberation and Inspiration

Ngũgĩ wa Thiong’o’s contribution transcends mere literary output.

He was a beacon for indigenous African languages, arguing passionately for their vital role in authentic cultural expression and intellectual development.

His work inspired generations of writers, scholars, and activists to question colonial legacies and champion self-determination.

His passing marks a profound loss for Kenya, Africa, and the global intellectual community.

However, his powerful voice, his uncompromising spirit, and his vast literary canon will continue to educate, provoke, and inspire for generations to come.

Final Words

In his final years, Ngũgĩ often spoke about the power of stories to liberate the mind.

“A story,” he once said, “is a battlefield of memory and hope.”

As Africa mourns the passing of a literary lion, the world is reminded that Ngũgĩ wa Thiong’o’s voice will live on.

In pages, in classrooms, and in the hearts of those who believe in the freedom of the human spirit.

ALSO READ: Kenya’s Hidden GBV Crisis: Survivor’s Story Reveals Systemic Failures