Fresh confirmations from internal contacts now place beyond doubt the accuracy of revelations that have for many years shed light on a deepening institutional malaise at New Kenya Cooperative Creameries (New KCC), with every irregularity flagged now being unequivocally corroborated by sources within the enterprise itself.

Insiders have affirmed that the narratives previously aired regarding administrative breakdown, financial opacity, and managerial disintegration were not mere allegations but direct reflections of the reality within the company’s crumbling core.

The recent disclosures by these informants paint a picture of collapse that no longer looms on the horizon, but it has arrived.

The company has begun to default even on the most fundamental of operational obligations: employees, among them extension officers, remain unpaid for extended periods.

Senior managers too, it is now reported, have gone months without salaries.

A notice has reportedly gone out advertising the vacancy of the Managing Director’s office, suggesting either an impending departure or a subtle acknowledgement that the current leadership arrangement has failed to arrest the enterprise’s nosedive.

Milk intake across the board has been so restricted that it borders on dysfunction.

What once operated as a lifeline for dairy farmers has now mutated into a bottleneck.

Those who relied on New KCC to offload their dairy produce now find themselves with no outlet, no recourse, and no income.

With payments to farmers interrupted, sometimes indefinitely postponed, this has left many of them not only destitute but also unable to service their credit obligations.

Financial institutions have responded the only way they know how: with asset seizures and threats of foreclosure.

It is not merely the institution that is disintegrating but entire livelihoods around it being obliterated.

Looking back, the signs were always present and increasingly vivid.

The chaotic relocation of the head office to the Dandora complex, executed with neither internal consensus nor logistical prudence, had already indicated the degree of disarray afflicting senior decision-making structures.

Complaints had circulated for months of salary deductions not remitted to statutory bodies, of insurance premiums deducted from payslips but never reflected in hospital systems.

It now emerges that these were not one-off administrative mishaps but part of a much broader collapse in the financial accountability of the institution.

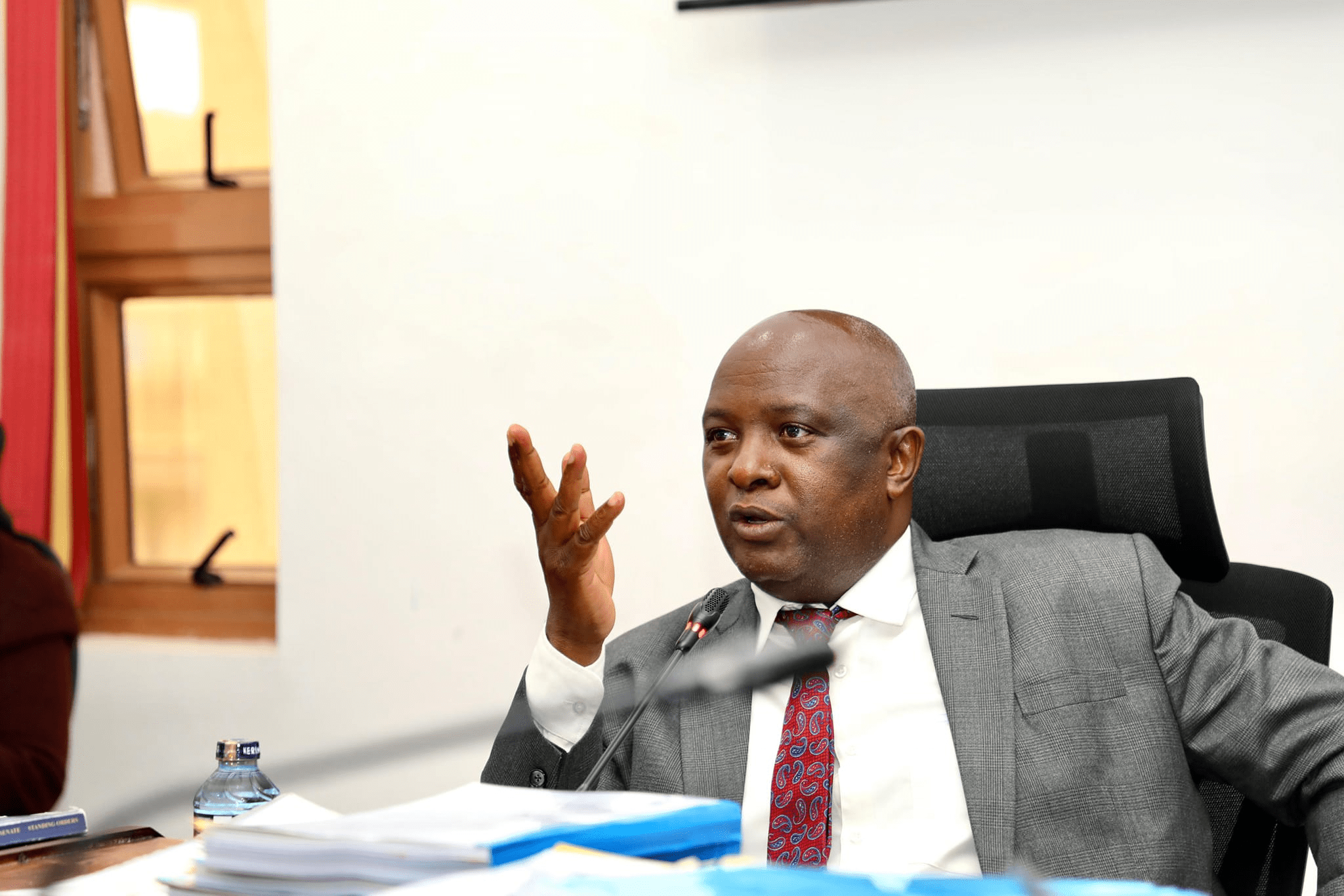

The tenure of Acting MD Samuel Ichura, which from its inception was marred by accusations of nepotistic appointments and opaque staffing maneuvers, seems to have presided over this final chapter of decline.

His continued recruitment of staff at a time when salaries could not be paid spoke volumes about priorities misaligned with the welfare of the organization or its stakeholders.

The internal ethnic rifts that worsened under his leadership, aggravated by lopsided hiring patterns, only served to deepen fissures in what was once a nationally symbolic agricultural entity.

A leaked audit report from the Office of the Auditor General had previously revealed a company so indebted that its liabilities dwarfed its assets.

Losses were declared to have reached Ksh 1.5 billion before tax by mid-2024.

These disclosures, rather than prompting public accountability or executive overhaul, were followed by even deeper silence from the boardroom.

Parliamentary committees are yet to receive any cogent explanation from New KCC on these matters.

Legal action from sacked employees is still crawling through the Labour Court system, unable to undo the institutional damage that has already occurred.

These insider disclosures do more than confirm the worst fears.

They suggest that the deterioration has passed the point of recovery under the current setup.

With core functions now compromised, procurement, payroll, logistics, farmer engagement, product distribution, New KCC may no longer qualify as a going concern under conventional financial metrics.

What was once a cornerstone of the country’s dairy sector is now little more than an emblem of what happens when public stewardship collapses into private interest and when oversight mechanisms fail to intercept managerial recklessness.

The story now is not merely about delayed salaries or mismanaged supply chains but about how a state enterprise, created to empower farmers and stabilize a key sector of the economy, has become a slow-motion case study in institutional self-destruction.

The people paying the price are not just bureaucrats in boardrooms but farmers, workers, suppliers, and communities who once built their hopes around this institution.

That promise, it now seems, has been fully betrayed.

We will keep pursuing every available lead, and as more information filters through from those still within the system, we intend to document the full extent of this unravelling until the last veil is lifted.