When Musalia Mudavadi warned youth against the reckless use of social media, his message was clear. Online behavior can cost you a job, a visa, or even your future. But for Albert Ojwang, it may have cost him his life.

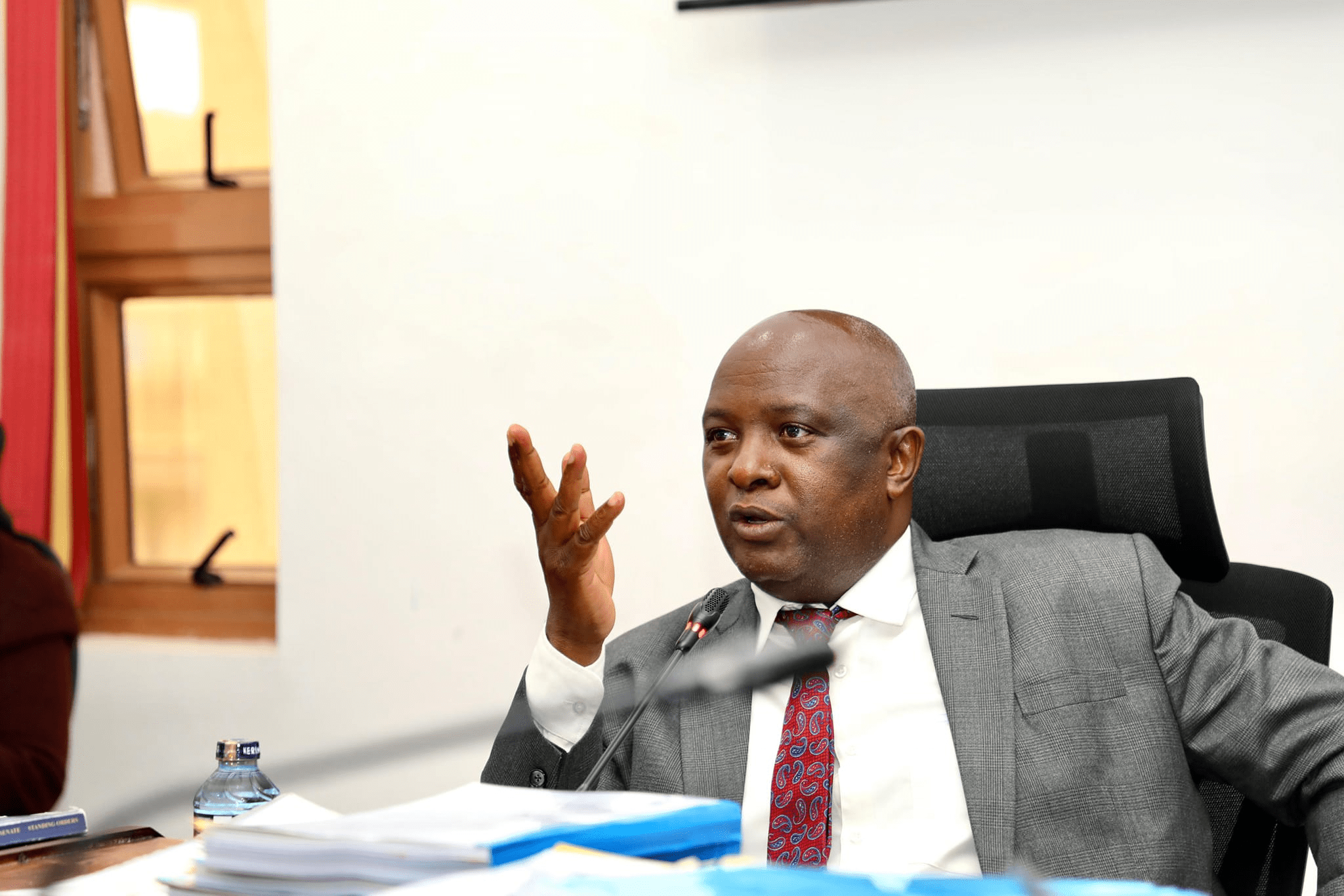

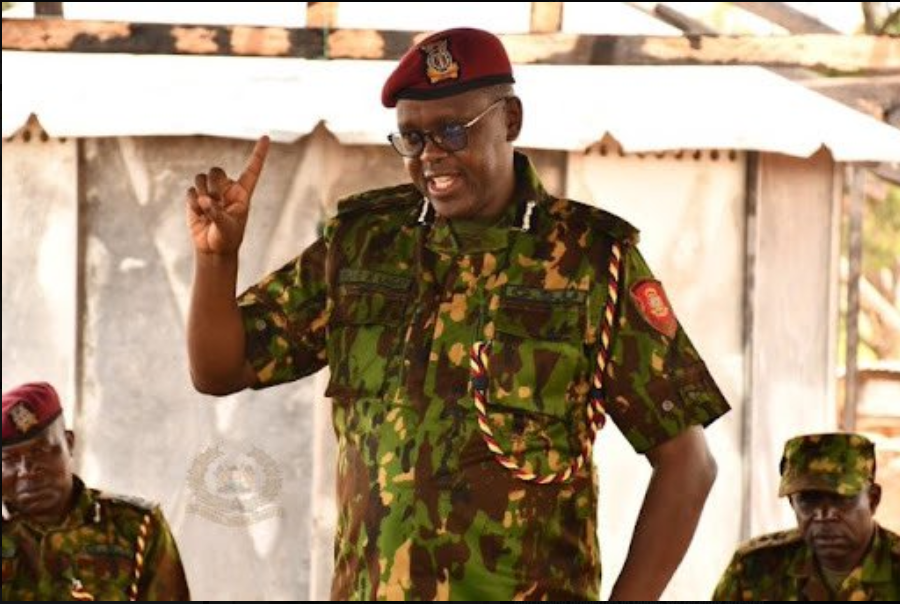

Ojwang, a young Kenyan with a growing online presence on X (formerly Twitter), allegedly posted comments linked to Deputy Inspector General (DIG) Eliud Langat. Days later, he was arrested. Friends say he was taken to Central Police Station on Saturday, never booked, and by Sunday morning, he was dead.

Govt Warning on Social Media Use Comes Too Late for Albert Ojwang

Close friends of Albert Ojwang say police picked him up on Saturday after he made comments critical of DIG Eliud Langat. They say the arrest was done in silence—no OB entry, no public record, just a man taken in and never seen alive again.

By Sunday morning, Ojwang was dead. Police now claim he “injured himself” in custody. But activists, legal experts, and citizens alike are calling that explanation a cover-up.

“How does someone get arrested, not get booked in, and end up dead 24 hours later?” asked one of Ojwang’s close friends. “This isn’t law enforcement. This is murder.”

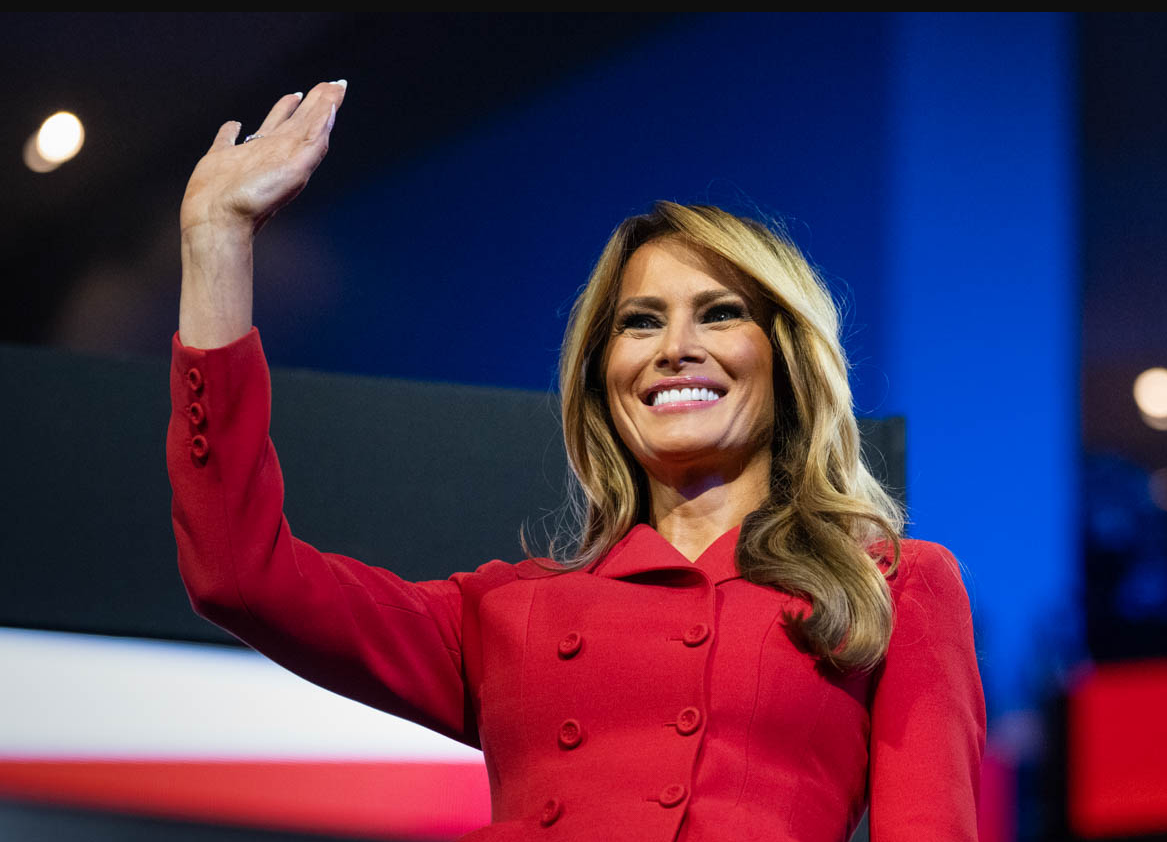

The arrest comes at a time when the government is doubling down on what it calls “reckless” use of social media. Mudavadi, speaking in Vihiga on Saturday, warned young people that their online history could be used against them when applying for jobs, visas, or government clearance.

He encouraged youth to act responsibly online, warning that the U.S. and other countries are developing frameworks to monitor digital footprints. But critics say that while Mudavadi’s message is about future consequences, Ojwang’s case is about the present abuse of power.

Fear Replaces Free Speech as Police Target Online Critics

Albert Ojwang’s death is not an isolated case. Over the past two years, a growing number of Kenyans have reported being harassed, arrested, or silenced for speaking their minds online.

What’s different about Ojwang’s case is the fatal outcome—and the silence from top law enforcement.

Human rights groups have pointed out that the lack of OB registration raises serious red flags. “If Ojwang was never booked, it means the police wanted no trace of him,” said a Nairobi-based civil liberties lawyer. “It’s a method used when someone is targeted—not protected—by the system.”

His death, allegedly caused by self-inflicted injuries while in custody, mirrors similar cases across Kenya where detainees “fall,” “hit themselves,” or mysteriously die before making it to court. These explanations are rarely challenged by internal investigations.

Instead of addressing Ojwang’s death, officials are pushing narratives about youth behavior on social media—effectively shifting the blame.

But free speech advocates say social media should not be policed with brute force. “If someone goes too far online, there are legal channels—summons, fines, community service—not secret detentions and death,” said a digital rights defender.

Calls Grow for Justice and Social Media Accountability Standards

Ojwang’s death has sparked demands for clarity on how Kenya polices digital platforms. Many fear that vague terms like “reckless usage” allow powerful individuals to silence criticism.

Musalia Mudavadi’s speech warned youth not to “shoot themselves in the foot” online. He cited risks like being denied visas or jobs for past digital behavior. He also referred to disturbing trends such as social media’s role in intimate partner violence.

But what about the state’s role in misusing power? Online platforms like X are spaces for free expression. While some users may cross the line, democratic countries have legal pathways to address this. Physical arrest—let alone death—should never be part of the equation.

Albert Ojwang’s family, friends, and legal advocates are now demanding a full independent investigation into his death. They want bodycam footage, police records, witness statements, and postmortem reports.

“This can’t be swept under the rug,” one of his relatives said. “He was arrested for tweeting. Now he’s dead. What happened in that cell?”

Kenya must now face a critical question: should warnings about social media behavior apply only to citizens—or to the police and politicians too?