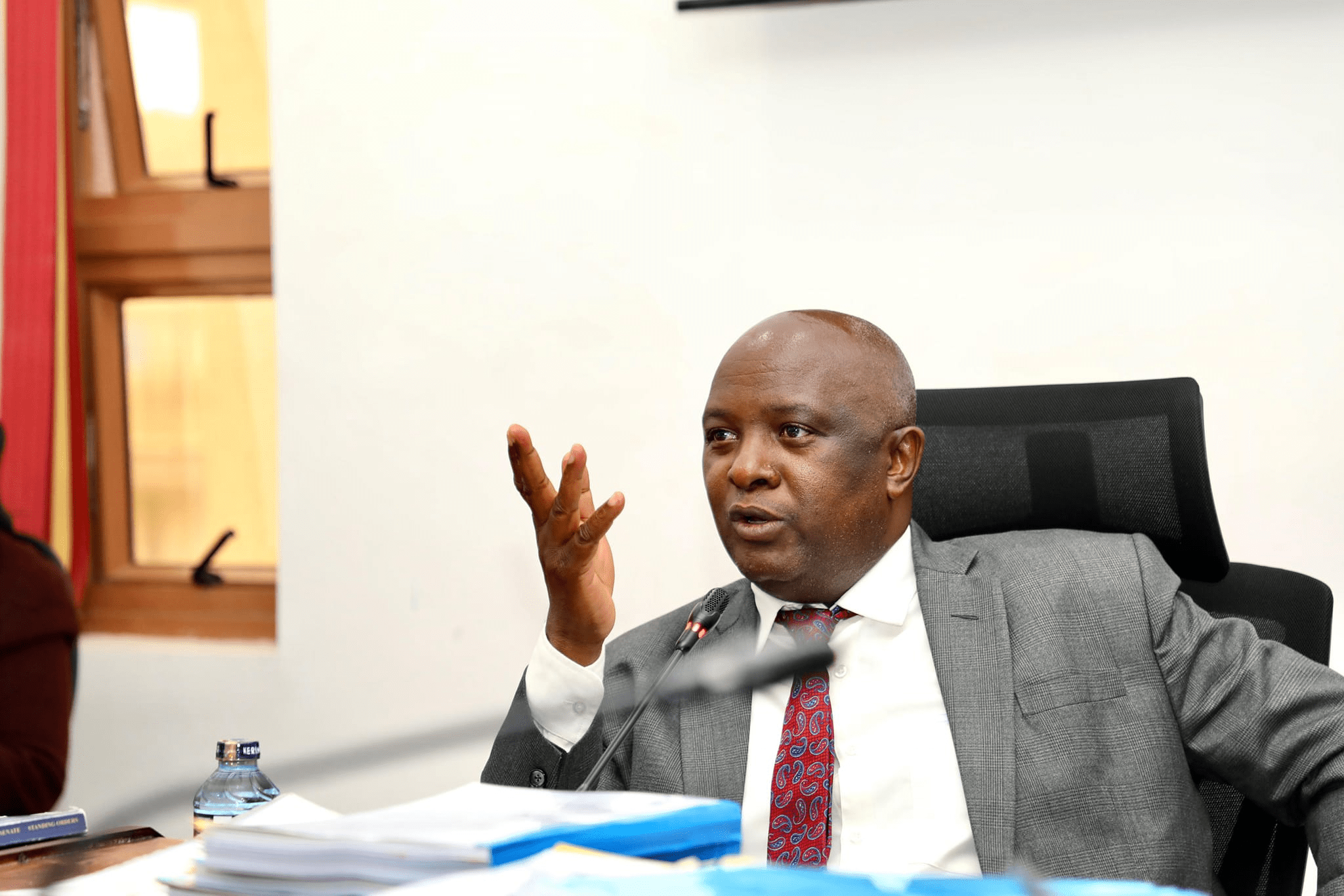

In an unprecedented move, Nairobi Governor Johnson Sakaja has sparked national attention by shutting down the iconic Freemasons Hall on Nyerere Road.

The clampdown, spearheaded by Health CEC Suzanne Silantoi and Revenue Chief Officers Priscilla Mahinda and Lydia Mathia, forms part of a sweeping operation targeting notorious land rate defaulters.

With Nairobi’s revenue under strain and only a fraction of landowners paying their dues, Sakaja is now wielding the county’s full legal arsenal.

But behind the Ksh19 million debt lies a deeper story about power, symbolism, and the struggle to make Nairobi’s elite accountable.

Sakaja Shuts Down Freemasons Hall Amid Ksh19 Million Land Rate Scandal

Governor Johnson Sakaja’s government is making headlines for locking horns with some of Nairobi’s most powerful institutions. On Wednesday, May 14, the Nairobi County Revenue Department clamped down on the Grand Lodge of East Africa’s Freemasons Hall for failing to settle land rates amounting to Ksh19 million.

The clampdown was executed by Health CEC Suzanne Silantoi and two Chief Officers — Priscilla Mahinda and Lydia Mathia — who insisted all legal steps were followed. These included issuing demand letters and final notices before moving in to enforce the law.

“This particular premises owes Nairobi County over Ksh19 million in land rates arrears,” said Silantoi as officers moved in to close the historic building.

Freemasons Hall is no ordinary address. Located on the strategic Nyerere Road, it serves as a headquarters for the region’s Freemasonry movement. For decades, its doors have hosted rituals, ceremonies, and meetings cloaked in secrecy and mystique.

By targeting such a prominent site, Sakaja is sending a bold message: no one is above the law — not even Nairobi’s most powerful.

The hall’s closure came just a day after the county government shut four buildings in the central business district for similar violations. With the county revenue system under stress, the crackdown is just beginning.

Why Sakaja’s Bold Move Signals a New Era of Accountability

Governor Sakaja is facing a financial crisis. With Nairobi’s wage bill ballooning and city services deteriorating, collecting unpaid land rates is now urgent. The statistics speak for themselves — only 50,000 out of 256,000 registered land parcels in the county are up to date.

The missing revenue has tied the county’s hands. Basic services like garbage collection, healthcare, and water delivery are under pressure. Public frustration is rising.

Sakaja’s administration has decided to act — not just through warnings, but with action. The crackdown aims to recover billions in unpaid rates that wealthy landlords and high-profile institutions have long ignored.

Freemasons Hall was a calculated target. Not only does it sit on prime land, but it also symbolizes a class that has historically operated in the shadows, often shielded from public scrutiny.

By enforcing the law against such an institution, the governor is tackling both revenue collection and long-standing perceptions of inequality in enforcement.

County Expands Crackdown Beyond Freemasons

The action against Freemasons Hall is just the beginning. According to the Revenue Department, the county is preparing to escalate the war on rate defaulters. This includes disconnecting basic services such as water and sewer systems.

CEC Silantoi was clear: clampdowns will not end with padlocks and police. “We are considering utility disconnections and more aggressive follow-up with major defaulters,” she told reporters.

Nairobi County’s Receiver of Revenue, Tiras Njoroge, added that several landlords had been given ample time to settle debts. Many, he said, had shown no goodwill.

The latest operation is one of several to follow. Dozens of buildings in the CBD and its environs are being surveyed for enforcement. Landlords and property owners are now on high alert.

Public Reaction and Political Undercurrents as Sakaja Shuts Down Freemasons Hall

Freemasons Hall is not just a building — it’s a lightning rod for controversy. Many Kenyans view freemasonry with suspicion, associating it with hidden power and secret deals. The hall’s closure has therefore stirred both praise and conspiracy.

But county officials are focused on facts, not symbols. They insist the clampdown is not political or religious — it’s financial. The Ksh19 million in arrears could fund multiple health clinics, sanitation programs, or school feeding projects.

Sakaja’s supporters see the move as long overdue. For years, ordinary Nairobians have watched county officials turn a blind eye to elite offenders. That era may be ending.

Critics argue that the timing is calculated — perhaps to win public approval as 2027 politics begin to take shape. But even they agree: enforcement is long overdue.