Telecommunications company Airtel Kenya is under pressure from industry observers and the public for not contributing its share to the Universal Service Fund (USF) a government initiative designed to bring mobile and internet access to remote and neglected parts of the country.

This comes as reports emerge that the company has been actively requesting the right to use infrastructure developed by other telcos, particularly for setting up its own masts.

Critics believe this approach takes advantage of investments made by rivals, without matching that effort through equal financial input.

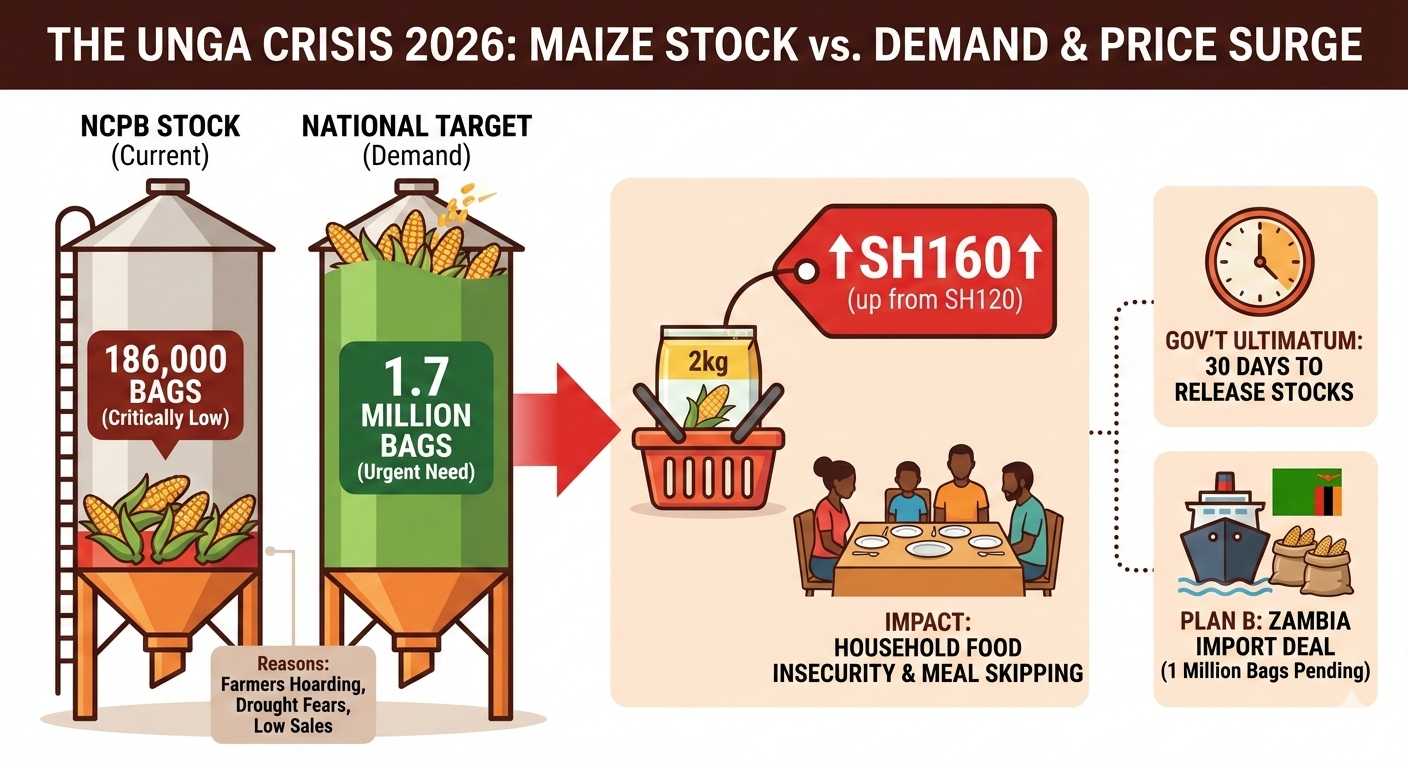

The USF was established by the Communications Authority of Kenya (CA) to fund projects in areas where it is hard to justify infrastructure development through normal business models.

These include places like Mageta Island, Baragoi, and parts of Northern and North Eastern Kenya.

The fund depends on payments from licensed telecom operators in the country.

So far, Safaricom has put in close to half of the total amount collected in the USF, close to Ksh 4 billion.

Telkom Kenya has also made substantial contributions.

These companies have accessed funding for rural mobile towers and have actively responded to calls by the CA to set up base stations in low-traffic areas.

According to the CA’s own data, Safaricom has accessed Ksh 880 million while Telkom Kenya has accessed Ksh 350 million under the scheme.

These numbers reflect not only participation but also a clear commitment to investing where returns may be uncertain or delayed.

In contrast, Airtel’s involvement in both contributing and bidding for the USF-supported infrastructure has remained minimal.

At the same time, the company has pushed for access to infrastructure developed by others, often citing the need to lower costs.

Industry watchers and digital rights advocates are now asking why Airtel is allowed to benefit from such installations without shouldering the initial investment.

Many believe that shared access must be earned, not demanded without financial participation.

Meanwhile, the CA’s new USF roadmap, a Ksh 40 billion plan spread across five years (2023–2027), is short of Ksh 12 billion, according to officials.

The strategy includes plans to expand network coverage to remote areas, create digital literacy programs, and support online content that reflects local realities.

Funding shortfalls could affect programs designed for women, youth, and people with disabilities, as well as rural residents who rely on mobile technology for services like health, education, and safety.

The CA has announced that it is looking into partnerships, donor support, and reinvestment by licensees to cover the gap.

Even so, telecom companies remain the backbone of this funding pool.

If major operators stay on the sidelines, the burden shifts unfairly onto those already contributing.

With mobile and internet services now a basic need, the debate over the role of each player in expanding access is growing louder.

Operators who dominate city markets are expected to step up in connecting villages, deserts, and forests, not just profit from existing urban coverage.

For now, all eyes are on Airtel, as the industry waits to see whether it will align its strategy with the broader national goal of a connected, inclusive Kenya.