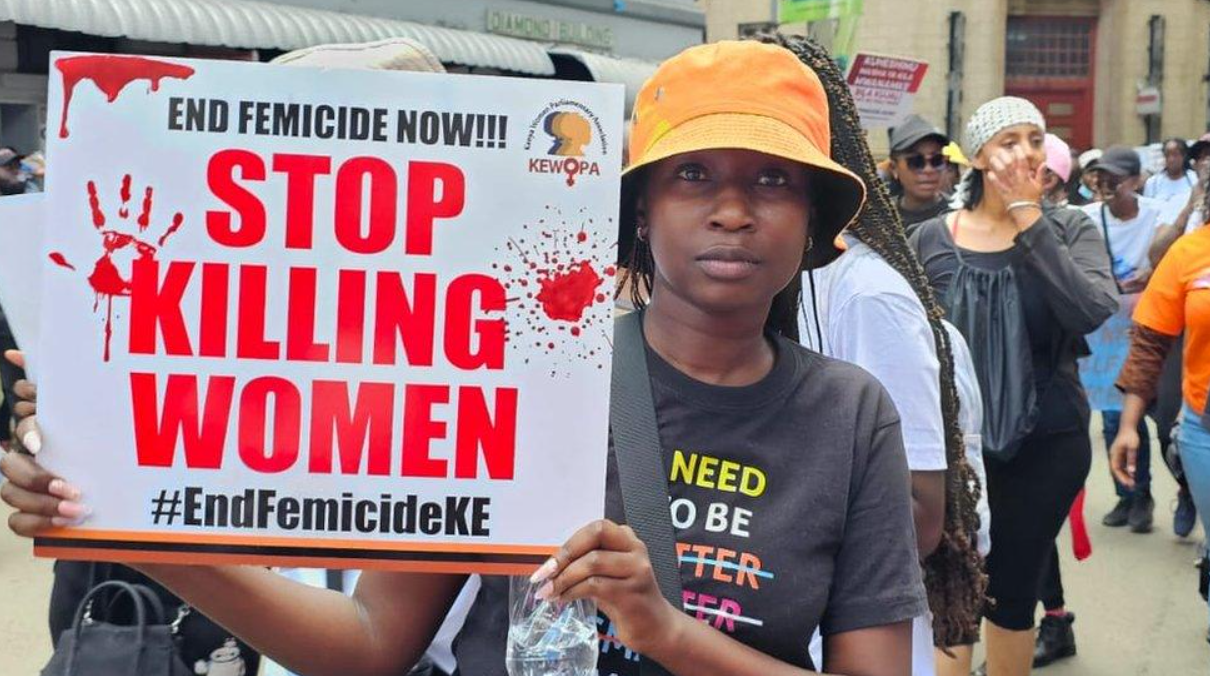

Gender-Based Violence (GBV) in Kenya is not just a statistic—it is a silent epidemic unfolding behind closed doors.

In alleyways, on public transportation, and within the very institutions meant to protect.

Beneath national headlines and fleeting government promises lies a chilling.

All-too-familiar narrative: that of survivors whose voices are drowned out by stigma, silence, and systemic failure.

A Story Too Familiar: Meet Grace

Grace, a 27-year-old mother of two from Kisumu, carries the scars of violence not only on her body but in her voice—soft, trembling, and heavy with stories untold.

“He hit me the first time when I was pregnant with our first child,” she says, referring to her former partner.

“I stayed because I had no money, no job, and I thought things would change.”

They didn’t.

For six years, Grace endured beatings, threats, and sexual violence.

Despite filing three police reports, seeking refuge with relatives, and even obtaining a restraining order, her abuser was never charged.

Her story mirrors thousands across the country.

According to the Kenya Demographic and Health Survey (KDHS) 2022, 45% of women aged 15–49 have experienced physical or sexual violence.

Often at the hands of intimate partners.

Yet convictions for GBV remain frustratingly rare.

Why GBV in Kenya Persists

1. Cultural Norms and Stigma

Deep-rooted patriarchal attitudes normalize violence against women, often framing it as a private matter.

In many communities, survivors are pressured into silence to “protect the family name,” and abusers are shielded by clan elders or religious leaders.

2. Weak Enforcement of Laws

Kenya has robust laws, including the Sexual Offences Act (2006) and the Protection Against Domestic Violence Act (2015), but enforcement is erratic.

Survivors often report that police trivialize complaints, demand bribes, or attempt mediation rather than justice.

3. Underfunded Support Systems

Safe houses, counseling centers, and legal aid services are few and far between, especially in rural areas.

Survivors like Grace often face the impossible choice of returning to abusive homes or ending up on the streets.

4. Data Gaps and Underreporting

Most GBV cases go unreported. Shame, fear of retaliation, and a lack of trust in authorities keep survivors in the shadows.

And without real-time data, policymaking becomes guesswork.

Grace’s Turning Point

Grace’s escape came not from state support, but from a women’s community group that gave her a small grant to start a tailoring business.

“I finally had the courage to leave when I knew I could survive on my own,” she says.

Today, she trains other survivors in tailoring and speaks at schools about violence and consent.

But not every woman gets a second chance.

What Needs to Change

Survivor-Centered Justice

Police, courts, and healthcare workers must be sensitized and trained to treat GBV as a criminal offense, not a family issue.

Increased Funding for GBV Services

Government and donor agencies must invest in safe shelters, free legal aid, trauma counseling, and economic empowerment programs.

Mandatory Data Collection

Kenya must create a centralized GBV database disaggregated by age, location, and type of violence to inform policy and track accountability.

Community Mobilization

Faith leaders, elders, and youth should be part of behavior-change campaigns that dismantle harmful gender norms.

Conclusion: A Call to Action

Gender-Based Violence is not a women’s issue—it is a national crisis.

Every story like Grace’s is a sobering reminder that behind every GBV statistic lies a life altered, a dream deferred, a right denied.

As Kenya continues to position itself as a leader in gender equality on global platforms.

Indeed, the true measure of progress will be felt not in boardrooms, but in homes like Grace’s—where safety, dignity, and justice are long overdue.

ALSO READ: Emmanuel Macron: Internet Erupts with Reactions as French President ‘Slapped’ by Wife Brigitte